|

|

|

|

My feet kept

getting worse. In the mornings I couldn�t get my shoes on, so I finally

asked for time off to heal them up. We had one American officer,

Captain Schultz, and a supposed Jap doctor. They easily agreed, and I

was off work for about a week. I couldn�t stand on my feet at all so I

crawled from place to place.

One night

the �White Angel� was giving his speech. �Too many men off work.� He

was going to inspect the sick himself. He always carried a long sword

so we all had respect for him. I had to walk in front of him so it took

a lot of nerve but I stood up and walked. The blood and puss squirted

out of my feet. He decided to send some men back and get replacements

so I think 30 of us out of 150 men went back to the main camp at

Cabanatuan. Later I heard that our Jap Commander had refused to let the

�White Angel� have any more men, after he looked us over.

I was on

detail for 6 weeks. Also I am sure this is where I picked up the shisto

bug or worm.

At the

main camp my feet healed fairly fast. After a month or so we heard of a

large detail to go to Japan proper. I was having trouble with swelling,

beriberi, that is. Also my tongue was sore, my mouth was cracked on

each side and my eyes watered badly, felt like they had sand in them.

Even got so I could hardly see over 30 ft. This slowly kept getting

worse. There was no cure for it there so I volunteered for Japan. Of

course, the story was more and better food, which again was a damned

lie. Bath facilities were none, but we had water in this camp. My

�Jungle Rot� was not getting better, also I was galled under my arms and

between my legs which didn�t seem to heal. I will carry these scars to

my grave.

During

this time we had cut the legs and arms off our clothing for laundry

purposes and also to have air on our sores. Our doctors told us these

sores would probably last until we got out of the tropics unless were to

get medication. These are the reasons I gambled my life to go to Japan.

Also,

again about the middle of October I had a severe case of diarrhea, felt

like dying for about a week but lived through, losing probably another

10 or 15 lbs. I would guess that I weighed about 120 lbs. when we left

for Japan.

Well

anyway, 1500 of us left for Japan on about November 6, 1942. We were on

the dock at Manila. There they divided us in three bunches of 500 each.

Each 500 men went into separate holds on the ship �Cattle Boat.� On the

one I was in it smelled from spoiled rice and had rats in it. Of

course, we soon out-numbered the rats so they didn�t have a chance.

This hold was about 30 x 40 ft. square. When they got about 425 men in

there it was full, so down came about 4 guards with fixed bayonets.

Soon there was room for the other men. I would say we had less than

two and a half

square feet per man. Now many of these men had diarrhea all the time.

No toilets whatsoever. It wasn�t over a couple of hour till this place

was stinking; also, there was hardly any ventilation. This was a Hell

Ship. I lost the name but it belonged to Marau Lines.

Well,

they dug up some benjo buckets or wooden pots holding about 15 to

20 gallons each. Soon they were full. How do you get them upstairs?

It was a mess. About as dirty on the outside as inside.

That

night, after dark, they decided they would let some of us up on deck. I

was one of the first up the steps. Tired as I was, I slept pretty good

on deck. Before daylight they herded us back in the hold. The first

morning there were six dead. After that it was about six to

eleven per day.

The

second night, soon after we got on deck, we heard distant explosions or

that�s what it sounded like to me. We were immediately ordered below

deck with bayonets again. We were being torpedoed by American subs.

Don�t think we didn�t have scared guards. We did not get hit.

The

following night I got on deck in time to see that we were being escorted

by several other ships. On a deal like this, a person sort of gets your

days and night mixed up because you don�t sleep until you get so tired

you have to. If you look around you, you don�t know who is alive and

who is dead. Furthermore your mind is so dull you really don�t give a

damn. Early on this trip I woke up and found a man dead next to me.

Later on this trip when I woke up a dead man had his arms around me,

mostly in the neck area. I could tell he was dead, didn�t know what to

do, didn�t want to cause any disturbance. I finally got that by apply

pressure enough I could move one arm. Finally I got loose from him.

We seemed

to have enough rice to go around on this trip. About 20% were eating

and the rest were not hungry.

|

|

-10- |

|

|

|

|

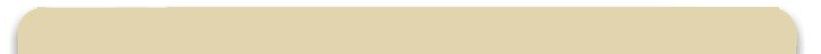

Machine gun training - The Ruhlen Collection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As I

calculate, on November 24, 1942, we landed in Osaka, Japan. There were

about 390 left of the 500. About 110 buried at sea. We unloaded at

night, walked to a large empty building where we slept. COLD! This was

a sudden change from the tropics and the �Hell Ship.�

The next

morning we were loaded on a train; road the big part of a day to the

town of Tanagawa. I don�t know what happened to the other 1000 men.

There was no communication. I am sure they got off the boat when we did

in Osaka.

The Japanese Army owned us

so they leased us to the Japanese Industrialists. We were unloaded

about dark, then hiked about two and a half or three miles to this newly

built camp. COLD! COLD! COLD! Temperature was

probably 45 degrees but we had no sleeves in our shirts and no legs in

our pants. No other clothes and no blankets. While we were

hiking out there it wasn�t quite so bad, also while we were walking, but

when we got there it seemed like we had to wait in line for the

interpreter, about two hours.

I got so cold I couldn�t even

shiver. I got so cold I couldn�t even shiver any more. I

was going to lay down but the guards were watching us closely. I

thought I would die in my tracks.

This interpreter, later we

called him �Grease Ball,� screeched at us for about half an hour, kept

telling us if we would work hard we would be fed well, which never

worked out. Well, anyway, I suppose at 11:00 PM, they issued us

some rice straw blankets and we went in our barracks. No heat of

any kind except body heat. I had lost all of mine. I froze

all night even under blankets. The next morning I couldn�t even

get up at all. I gave away my rice. A couple of men next to

me their blankets when they went to work. I had 15 or 20

blankets on me, still I shivered continually.

This kept

on for at least 10 days. The guards would get me up days and try to

force me to work and all I could do was shiver and fall down. I lost a

lot of weight on this deal again. I think they call this hypothermia

now.

In about

two weeks they started a sick room in another barracks. I was moved

there. It was a lot of relief not looking at a bayonet once or twice a

day and being threatened with it.

I believe

they did have a small stove there. I finally got to eating again, a

little at a time, but it took at least two months before I could walk

around outside. By this time I had malnutrition and beriberi so bad

that my legs felt like a couple of fence posts most of the time. While

this was all going on, my jungle rot and galling had healed up. My

tongue and mouth cracking got worse. My mouth would heal and then would

crack again a little higher. The old crack seemed to move a little

lower each time.

Some

after we arrived in Tanagawa, the Japs issued us each an old worn out

winter uniform. They had a lining and plenty of louse eggs. After

wearing them a couple of days, they would start hatching. This was our

first bout with lice. When spring came finally they issued us summer

uniforms. No lining and very few louse eggs. So from then on we had a

uniform change, fall and spring, winter with lice and summer without.

However, in summer we had a lot of sand fleas that were impossible to

get rid of.

After

getting outside a few days and standing in the sun each day, I got to

eating better. My strength slowly returned, to a degree. That is why

the Japs worshipped the sun, I soon learned.

Anyway it

wasn�t too, probably March 1, 1943, and I was back in my first barracks

and on the labor detail. I think I had a ribbon of some kind that meant

light duty. After about three or four days a Jap guard jerked that

off. Don�t think I weighed 110 lbs at this time. I was very weak, got

kicked and slapped almost daily. These Jap guards always took it out on

the weak ones. They wanted more production. The Jap

Honsoes were not

supposed to hit us. They were the Jap work bosses. However, they could

make a lot of noise until a guard showed up when someone shirked or sat

down. The Jap army owned us. They had no mercy.

This camp

was on a job project building docks for submarine dry docking. We were

moving a mountain into a bay. We had dump cars running on narrow gauge

tracks. I think they were probably the U.S. and were worn out in coal

mines. Here they were pulled by a mine mule. I have been around coal

mines in southern Illinois and they looked the same to me. These tracks

were technically laid. These cars would take about the same power down

grade loaded and up hill empty. Two men to a car, for a healthy man is

was hard work but it could be done. The average haul was maybe one

mile. The mountain was about half rock and half dirt or clay.

The Japs didn�t know what Sunday meant. We were supposed to have

the first and the 16th off work. These were what they called their

Electric Holidays. Also on these Yosima (rest) Days, we were supposed

to get a cigarette issue of ten cigarettes. As time went on they forgot

the cigarettes and later on forgot the Yosima days, at least half of

them.

I

struggled on from April through July, then somehow I got a bruise on my

right hip. Don�t know what from. I kept working and it kept getting

worse. They, the Japs and two American doctors, did get a sick call

established occasionally. They even got a few supplies far old

fashioned for our doctors. This bruise swelled badly, finally got as

soft spot in it. It was like a lump jaw cow. I went on sick call that

night after work. A Dr. Campbell from Oregon asked me what I was

waiting for. I told him �that soft spot.� It had been hard

before. When we went into sick bay he had three men hold me in a

corner standing up. I said, �Cut it low, Doc, I want it to drain.�

He looked at me and said nothing. They had sort of a half moon

funnel which a corps man held against my leg. The doctor did a

good job. Later they told me they got at least one and a half

pints of puss out of my leg. They bandaged it up the best they

could. I asked the doctor about a day off. He said, �No, we

have too many men working that need a day off worse than you do.�

I worked two more days, but could not keep a makeshift bandage on it.

By that time there were little blisters all around the incision. I

went to work one day and that night I again went to sick call. It

looked like raw beef steak. The doctor agreed I should have had a

couple of days off; so he got me in the sick room immediately, gave me

what treatment he could and about three days rest. I was OK again.

|

|

-11- |

|

|

|

|

Training Shoot at Battery Hearn - The Ruhlen

Collection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Well, I

struggled away, nothing good or bad ever happened that I can remember

until about November, 1943, then I got pneumonia. I lay for days in a

coma. I didn�t know what was wrong and didn�t care and the doctor

didn�t tell me until I showed signs of improvement. Then he told me he

wasn�t expecting me to live anyway. During my period of pneumonia, our

one doctor died sudden like. Can�t remember his name. Our remaining

Doctor Campbell said it was a stroke. This Doc Campbell had a Captain

rating. Always said he didn�t like to be called Doc as that was

something they tied boats to. He was a young doctor, not over 30.

When I

was about over pneumonia, don�t remember if I had gone back to work or

not, but I developed my first Yellow Jaundice. Seemed like the weaker

you are the more subject to these diseases you get. After being sick

this much in Japan, I didn�t feel any worse much, but my urine was like

syrup for a long time. My eyeballs were yellow. Must have been

January, 1944, when I got back on the job. Again it was COLD! COLD!

COLD! to me. We were right on the bay, it froze very little there, but

it was my condition. No heat and not enough clothes. The wind seemed

to be damp, coming off the ocean. Of course, I was not the only one

sick, there were plenty and a lot of them died. In Japan they were all

cremated, to my knowledge.

On April

20, 1944, the Japs had a big shakeup. There were too many sick,

according to the Japs, so they sorted off the weaker ones. I was among

them. They sorted off 100 weaklings, although some of the sickest

stayed. I think it was one Industrialist trading horses with another

Industrialist. Anyhow, the Japs did the sorting, told us we were going

to a Yosimay Camp. Of course, we were used to their jokes by this time.

We were

loaded on a train a few miles from there. We were on this train about

20 hours. Then we arrive in Aomi, Honshu. I think this left 225 men at

Tanagawa, so we lost about 65 men in this 17 month period. When you

leave a camp like this you never hear from it again.

This camp

was a lot further north. When we got there we could see lots of

evidence of snow. It had just melted. We were hiked about the usual

three

miles to camp. When we got there we were �WELCOMED� by about 450

Englishmen. They had been captured at Singapore. They were there about

one year. There were 550 to start, but they had lost 100 men. �Limeys�

we always called them; they even liked that name. There were a few

Australians, a couple from New Zealand, the rest from Ireland, Scotland

and England. At first we had problems understanding them; but if they

talked slower we could understand them a lot easier than the Japs. They

had three officers, one was a minister and two were line officers. They

also had one older American Navy doctor. Never did hear where they got

him. He was probably 65 years old and too feeble to take care of the

sick ones. This minister was also in bad shape, with legs swollen with

beriberi, but between them they tried to run the M.I. room, as it was

called from here on out.

Hair cuts

and shaves were hard to come by. The Japs made no provisions. Hair

clippers, scissors, razors, even pocket knives were taboo. Even pencils

and paper were out. Every so often they had a shake-down inspection.

That meant you carried all your possessions out in the yard and

displayed it. One bunch of guards through it while another bunch went

through the barracks looking for anything left. If they saw anything

they wanted or illegal, they just took it. You probably got hit over

the head on top of it. However, there were still a few scissors and a

few sharp mess kit knives around, so on Yosima Days, if we weren�t too

sick, we�d cut each other�s hair, quite often shaved our heads at the

same time. Soap was also a very scarce item. We probably got sheared

once every three months at either camp.

This

Limey Camp worked rock quarry and smeltering furnace, made iron ore.

They told us it was low grade. They sorted out the largest and

strongest men for the furnaces, �dento� that was. I was too weak so I

wound up in the rock quarry, again on these �toros� or dump cars on the

narrow tracks.

Well, it

was spring and things went along quite well for awhile. My beriberi was

bad, swelling mostly. Seemed as though my kidneys didn�t work when I

was up walking around, then at night when I lay down I had to get up to

urinate every 45 minutes. Either my bladder was inflamed or it would

not stretch. I didn�t think it held a cup full of urine. In the

daytime I just didn�t urinate.

|

|

-12- |

|

|

|

|

|

![]()