|

After

my January trip I contacted John Lindgren for advice, and he mailed me the maps

I needed to follow the 503d. Jim Mullaney also provided me information

from notes he kept on the battlefield, as did the writings of Chet Nycum and

John Reynolds. I must mention that I was specifically looking for

the route of G Company, my father being in its Third Platoon. An additional

consideration in tracking G Company is that from May 13 to May 26, 1945, Third

Battalion was left in the mountains with the 185th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Infantry Division, while

First and Second Battalions deployed about fifteen miles south, through Murcia,

to attack in the direction of Hill 4055. This meant that Third Battalion

records were kept by the 185th Infantry Regiment for those two weeks.

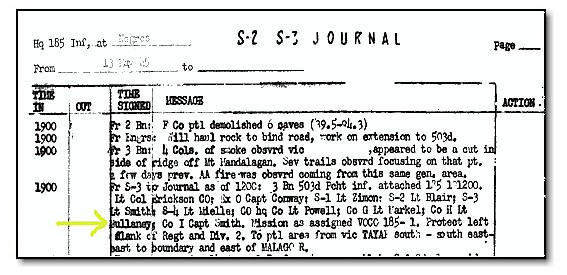

In July 2004 I traveled to the National Archives in Maryland and found and

photocopied the S-2/S-3 journal of 185th Infantry Regiment for the Negros

campaign. Third Battalion activities were well documented in this log.

On 13 May, 3d Bn 503d PRCT, linked up with the 185th Infantry and remained

in the mountains, whilst the 1st and 2d Battalions were deployed to attack in

the direction of Hill 4055.

My goal was to reach the areas called

�high ground� and �incident� on the GPS map. The 503d fought for the �high

ground� from April 21 through April 28, 1945. After taking it, the Japanese

began to fall back quickly into the mountains. In the area labeled �incident�

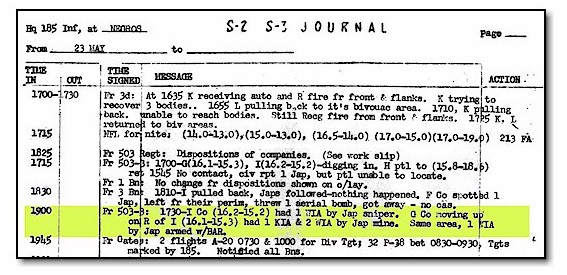

my father was involved in a mine explosion on May 23, 1945, described in the 185th

journal. One trooper, Fred Blomfield, was killed by the mine, and two others

were wounded. My father was shielded by a tree and not injured.

I plotted coordinates for G Company

movements from 503d and 185th records on the maps John Lindgren had

provided and got a clear picture of the company�s route. I then converted some

of the plots to latitude and longitude for use with the Global Positioning

System (GPS). Having GPS with me was essential. There are no current maps or

clear high resolution aerial photographs of the battlefield area available The

Philippine Mapping Agency, Fort Bonifacio, sells map sheets derived from

US Army publications of the mid-1950�s, which were based on aerial photography

dating from 1947. Although the topographic information on them is still

valid, most mad-made features have changed substantially. Further

complicating navigation is that Filipinos generally use different names for

landmarks than what is in the military records. With GPS I always knew

exactly where I was. I had programmed reference points such as villages

and mountain peaks into the GPS before the trip.

On my September trip I hired a

Jeepney to first follow the 503d invasion route, the Tokaido Road, as far as

possible. We drove from Silay to Hacienda Hinacayan, now a small village, the

kick off point for the 503d on April 9, 1945. An unmarked sugar cane road

leading southeast out of town is the Tokaido Road. I expected to find a

railroad track for reference, but the locals told me it had been removed by

Hawaiian Pineapple Corporation. They did show me the track bed. My guide said

we could not follow the Tokaido Road past Napilas, as no established hiking

paths exist.

I then had two options to get to the

503d main battle area. Walk in via established paths beginning from Japanese

shrines shown on the GPS map, or drive in via a sugar cane road that goes east

of Talisay to the foot of Hill 3155 (also called Dolan Hill, after Lt John

Dolan, commander of Company C, 160th Infantry Regiment, 40 Infantry

Division, killed there on April 20, 1945). I chose the driving trip. We could

only make about five miles per hour over this extremely road, but arrived

conveniently at 2000 feet of elevation, at the base of Hill 3155, labeled

Magcorco on the GPS map, before having to walk. Unfortunately, as we were ready

to walk into the area, heavy rains arrived and prevented me from going. The

rain was so frequent and heavy I decided it would be better to come back during

dry season, rather than rehire the guide and vehicle the next day. Also, the

sugar cane fields are burned during dry season which would improve visibility.

I learned a few lessons on these

trips. First, you must bring all information with you. Nothing specific is

available locally regarding the 503d. Second, GPS is ideal for exploring the

battlefield. I can't emphasize enough the importance of having GPS on a

trip like this. It is physically difficult to travel anywhere on this

battlefield, and it is nice to know exactly where you are when you are investing

a lot of effort to move around. GPS eliminates reliance on using names to

navigate. The Filipinos use local names that usually differ from military

records, and compounding the problem is that my guide didn't speak English very

well, as will be true of many of the people living in rural Negros. Another

problem is that the Filipinos are not used to using maps. When you live your

whole life within a few square kilometers, you don't need to learn map reading.

The sugar cane fields, dirt roads, mountain peaks are difficult to distinguish

with the lack of current maps or aerial photography. Obtaining information

from locals is unreliable because of problems with names. For instance, there are seven different settlements named Napilas in the vicinity of Silay. They are all likely derived from a single

extended family, but this guarantees confusion if you ask for directions.

I plan to make one more dry-season

trip to finish exploring the battlefield. A guide suggested a walking trip from

the Japanese monument area along �Secret Trail� to Murcia. He told me this

takes two days for a �strong hiker�, with one night spent in the mountains. I

will be satisfied to reach the limits of the Third Battalion�s movements, which

is near the spot labeled �incident� on the map. I may also go to the foot of

Hill 4055, by vehicle through Murcia, to at least see the terrain of 503d

operations which occurred there from May 12 through June 7, 1945. I may also

try to find the spot of Gen Kona�s surrender at Hacienda Santa Rosa. There are

likely people in the area who would know where the ceremony occurred. Another

possibility is chartering a private airplane to fly over the battlefield and

take some high quality aerial photographs.

Prior to my visit, I did some research regarding the sugar industry on

Negros. It is not a pretty history. The labor policies are right out of the

middle ages. To avoid minimum wage laws the sugar cane is sometimes paid for as

piecework or by kilogram. I was interested to see that the US gave the

Philippines special status following WWII regarding sugar shipments to our

market. The idea was to help the Philippines recover from the war. This special

status continued through the 1970s, probably for domestic political reasons. Although it did make a few people wealthy,

the net effect was damaging both to the industry, and to the community. Because

they had a guaranteed market, the owners lost interest in modernizing. They also

put marginal land on the mountain slopes into production because they knew they

could make a profit selling into the US market, even though this led to erosion

problems. When preferred access to the US market disappeared because of changing

market conditions and politics, the industry on Negros was uncompetitive in

comparison with the

more mechanized production in other countries. To this day they compensate by

paying absolutely bottom level wages. This leads to the social problems which

breed the NPA etc. Local authorities have tried to get sugar cane workers to

diversify what they plant, and to learn other skills, but old habits die hard. If their father worked sugar cane, the children do also.

Virtually the only way to break the cycle is to get an education.

Finally, don�t go to Negros during rainy season. It not only rained each

afternoon, but at night as well. The rain was so heavy one night it sounded

like a freight train passing through my hotel. I wonder how it sounded under

my father's poncho.

Steve Foster

|