Not

until he arrived did

he finally find out

what he was there

for. The mission was

to locate and

hopefully recover

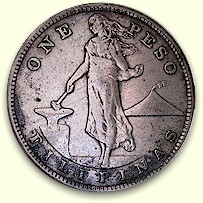

270 tons of silver

pesos, valued at

$8,500,000, that had

been dumped into

Manila Bay off the

island of Corregidor

by orders of General

Jonathan Wainwright

in April 1942, when

the surrender of

U.S. forces to the

Japanese appeared

imminent. Gold,

securities and the

silver coinage had

been brought from

the Treasury in

Manila to Corregidor

before the city was

ceded to the

Japanese invading

forces in January;

the gold and

securities had

departed with

General Douglas

MacArthur to

Australia on the

famous PT boat, but

the silver was too

heavy to move, so it

had been carefully

boxed up and dumped

into 130 feet of

water in an area

between Corregidor

and the mainland.

The site was

carefully surveyed

at the time, but in

the terrific

destruction caused

by the bombing and

shelling of

Corregidor, all the

landmarks had been

blown up. In an

interview he gave on

the “Engineer Show,”

a radio show

broadcast from Fort

Belvoir, Maryland,

Anderson’s home

base, shortly after

the war ended,

Anderson explained a

little more

thoroughly:

Anderson: Here

at the Engineer

Board, we had

developed an

underwater mine

detector that we

were anxious to

test in tropical

waters. And when

we were asked to

aid in finding

the treasure, I

was send to

Manila to… well,

you might say,

kill two birds

with one stone:

first, find the

silver and

second, test the

detector.

The Interviewer

(an officer not

otherwise

identified named

Warren): Then

your job was to

find the stuff.

Who actually

recovered it?

Anderson: You

can give credit

to the 1054th

and 1059th

engineers Port

Construction and

Repair Groups

and Navy Ship

Salvage Units

for bringing the

silver up.

As

part of a Joint

Army-Navy Port

Repair and Salvage

Group, he shortly

boarded the

Submarine Net Tender

Teak (“All

net tenders are

named for some kind

of wood,” Anderson

tells the

interviewer), which

was fully equipped

for salvage. “There

were no officers’

quarters for me, the

only army officer,”

Anderson recalls in

another memoir, “so

they rigged a big

tarpaulin on the

foredeck with an

army cot; of course

I took my meals in

the wardroom with

the rest of the

officers.”

Recounts Anderson,

“Using a technique

Schlumberger had

described to us for

finding metals in

seawater, I borrowed

the 50-microampere

multimeter from the

radio room and built

the Schlumberger

apparatus. We soon

located the silver.”

Warren: Did you

have any trouble

in locating the

pesos?

Anderson:

Plenty! It seems

the original

charts were

misplaced. And

local natives,

who had probably

seen the silver

dumped, had been

diving for it

with some

success. Of

course, we

investigated,

but found only a

small amount

where they were

working.

Warren: In other

words, they

hadn’t found the

main treasure.

Anderson: That’s

right. The only

thing we could

do was survey

the entire area

of Manila bay

around

Corregidor. We

found it

impractical to

send a diver

down 110 feet

with our

portable

underwater Mine

Detector Set, so

we rigged up a

device I call

the “Slido Wire

Potentiometer.”

Warren: Sounds

highly

technical, Lt.

Anderson.

Anderson: It’s

really simple…

an electric

cable with a

copper ball at

the end was

suspended to a

point six feet

from the bottom

of the bay. As

soon as it came

near the silver

metal, we got

our reaction and

a reading on the

“Potentiometer.”

Then a diver

went down to

make sure.

Warren: And if

he found silver?

Anderson: We’d

anchor, using

four cardinal

direction

anchors so that

fine adjustments

of the ship’s

position could

be readily made,

and, under the

supervision of

the Navy, begin

to haul the

pesos up… What

we did was to

drop a line with

a GI [garbage]

can tied to its

end and the

diver, using a

bucket, would

fill the can

with silver. It

was tough work.

Using hardhat

diving suits,

the diving team

could only stay

down about 30

minutes. They

would then have

to spend 45

minutes, in

three stages, to

decompress on

the way back to

the surface. Yet

each haul,

weighing about

500 pounds,

netted about

11,000 pesos, or

$5,500.

Warren: You say

they had to use

a bucket. I

thought the

money was

dropped in

boxes.

Anderson: It

was. But

tropical worms

had eaten

through the

wooden boxes and

when the divers

touched them,

they

disintegrated.

The silver

spilled out all

over the muddy

bottom.

Warren: I always

thought

recovering

treasure would

be more

exciting.

Anderson: Maybe

it would be, if

it was finders

keepers, but as

it turned out,

it was just

another job for

us. There was an

M.P. Security

Officer, Lt.

Hagerman, on

board who saw to

it that we

didn’t pocket

any fortune.

Believe me, he

didn’t watch us

any closer than

we watched him.

And the M.P.’s

came every

second day and

returned the

pesos to the

Treasury.

Besides, the

salt water had

corroded most of

the pesos, and

before they

could be used,

they’d have to

be melted down

and recoined.

Said

Anderson in a more

recent memoir, “When

I drew my last pay

in the Philippines,

I was issued some of

those coins, though

by that time

everybody had a bag

of his own. I still

have two left.”

Lt.

Anderson supervised

the recovery of

nearly $3,000,000

worth of pesos,

which were presented

to the Treasury in

September 1945. The

work continued for

some months

thereafter, but the

full amount was

never recovered. In

addition to the

local divers’

depredations, an

unknown amount had

been recovered by

the Japanese and

shipped out in two

boats, which were

later sunk.

—Sara

Collins Medina