|

A.P.O.

704

- 2 -

Gifford said thirty to forty Japs

had run out of the battery just before the flames erupted.

Along with the Americans, they had raced shoulder to shoulder toward the cliffs,

with only one thought in mind for this brief moment.

That single thought was to escape the terrible tongues of flame which were

reaching out seeking to engulf them.

One D Company man, Pfc. Thomas T. DeLane was killed.

One man broke his leg and was dragged along by his buddies in terrible

pain. It was later determined that

about 65 Japs were incinerated inside the battery.

It was quiet in our sector, as

though the war was over.

Battery Wheeler was dead.

There were no machine guns in Crockett Ravine.

There was not even an occasional Jap popping up out of nowhere to shoot someone

in the head. No sniper bullets

rattled your eardrums as they cracked within inches of you head.

The 850 Japs must be dead.

Todd and some of the others picked up souvenirs, but I could not develop any

interest. Some of the mortar men from their position near Building 28-D

came out and took pictures standing beside the old M-3 AA guns. I was tired,

dirty, hot, and thirsty, and if it crossed my mind that as 1st platoon commander

I should commit my thoughts to my diary, there was always something more

important to do. The next entries

appear only after we got back to Mindoro.

All this after only two days and nights.

The 1st Battalion arrived

yesterday afternoon and with them were my six missing men: Staff Sergeant

Charles M. McCurry, Pfc. Marion E. Boone, Pfc. Ralph E. Iverson, Pfc. Paul A

Narrow, Pfc. Theodore C. Yocum and Pfc. Bill McDonald. Near noon we moved back to Officers Quarters 28-D.

We were issued 2 or 3 K-rations and a canteen of water.

This was the second canteen of water we had received on Corregidor.

We had jumped with two canteens full,

so that in all, we had four canteens of water issued to us to see us

through the first three days on Corregidor.

Actually we wouldn't get more water until the next day, 19 February. This

would be about the middle of the afternoon when we reached the long barracks.

The

company history does not give the date nor circumstances of the death of Pfc.

William W. Lee. The 2nd platoon was withdrawn from the NCO Quarters the

morning of the 18th. They moved in

and around Officer's Quarters 27-D. Lee

and several others were in one of the first floor rooms. Lee slipped off his webbed harness and let it slide to the

floor. Speaking of Ed Flash's 'Hornet's

Nest' from which he had just come, he exclaimed, "Boy, I'm glad to be

out of there!" He lay down on

the floor, put his head on his musette

bag and, as he did, a

large chunk of concrete fell from the wall, crushing

his skull and killing him.

The

1st platoon was given the mission of capturing one of the Batteries far out on

the western end of the island. I

now know it as Battery Smith, for I know the names of all the Batteries today, but at that

time we did not know the names of many of the batteries until we were close

enough to read them, if that was possible. The same goes for the names of the

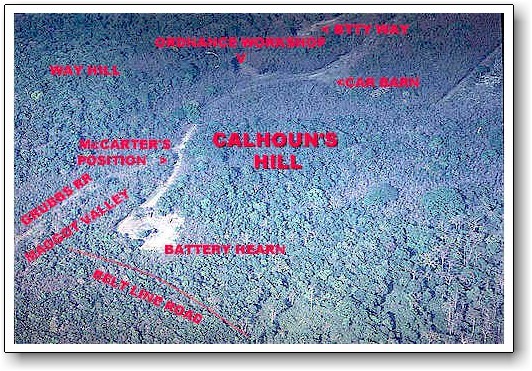

hills. What are today Way Hill, and Hearn

Hill were in those early days, 'Bailey's Hill' or 'Calhoun's Hill,' often

spoken with a pointing gesture in the air in the general direction of the

feature.

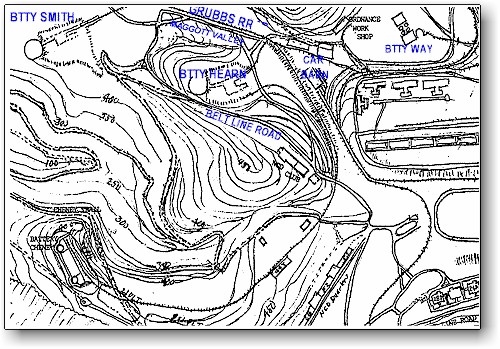

The

briefing

was given on a barely adequate map, since the area was far out of sight.

There were no adequate maps on Corregidor, and even the maps we had did not

identify the batteries, so it was a case of making do with what we

had. There were no provisions for supporting fire.

We had only the platoon SCR-536 radio, so we would be out of

communication, for we had learned by experience it would be another case of

"out of sight, out of contact."

I was to follow the trolley tracks to first of the batteries (Hearn),

turn west, and follow the ridge to the objective.

The nearest troops would be the remainder of F Company upon

Topside about 700 yards away, but with no reliable way to contact them should it

become imperative.

In

addition to drawing water and rations we replenished our ammo supply.

Fortunately the supply of ammo was plentiful.

The riflemen filled the pouches on their rifle belts and some picked up

an extra bandolier of 8 clips. Thus

they all had 128 rounds of ball and some had 192 rounds.

The BAR's and TSMG's were equally well supplied.

There were no machine guns or other supporting weapons attached.

The

Company left before we did. They

were going to the west end of the long barracks.

We waited until C Company moved in to relieve us.

They also relieved D Company at Battery Wheeler.

We

moved out following the trolley bed. The

tracks had been removed near Battery Wheeler.

We moved to the northwest, below Topside. The area was wooded, having escaped heavy bombardment.

As a consequence we had to move cautiously, pausing to investigate

suspicious areas. There were a

number of parallel tracks leading to a car barn, but we followed the tracks west

of these. This set of tracks was in

a cut with concrete walls. We moved along the east side of the cut until we came to a

cut-down where we could go down through the concrete walls and up to the other

side. The cut-down was well

constructed with concrete walls. Down

at the track level we could see that the railroad cut deepened as it ran to the

northwest. The walls appeared to be

12 to 14 feet tall. The cut curved

on out of sight to the left. After

we climbed up to level ground on the west side of the cut we could see the bare,

bomb-scarred hill which covered the Battery Hearn Magazine.

No foliage was left.

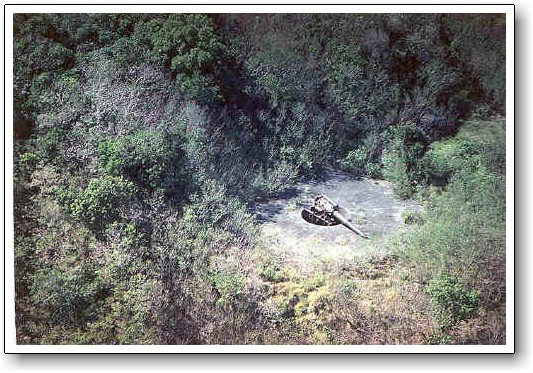

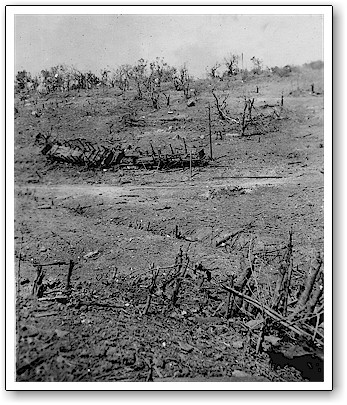

Battery

Smith. The jungle always wins. (Photo by courtesy of Al McGrew)

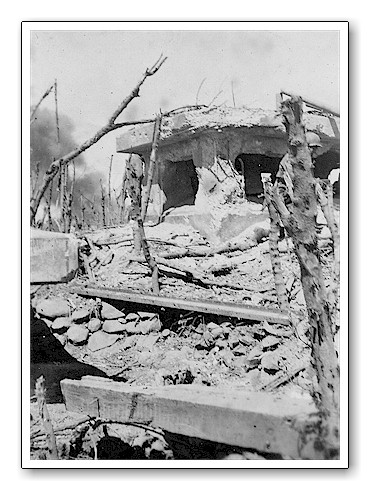

Battery

Hearn. The hill atop the magazine at the rear is now overgrown. (Photo by courtesy

of Richard Marin)

Both

Batteries Hearn and Smith were 12 inch barbette mounted guns, 340 yards distant

from each other. They sat in the

middle of huge, round concrete pads. This

gave them the appearance of bull's-eyes since they were out in the open.

Adjoining the concrete pad to the east of each gun was its magazine,

which was covered with dirt forming a fair sized hill.

The man-made hills had very steep sides on the north, west, and south.

The east side of Smith was steep but not so severe as the other sides.

The east side of Hearn was more of a gentle slope which was easy to

ascend.

Originally

Smith was Battery Smith 1, and Hearn was Battery Smith 2. They were less formally known to the men of pre-war

Corregidor as the Smith Brothers, Pat and Pending (after a popular radio

commercial of the day) and in their day they presented a fearsome twosome. Because of their barbette mounts they could elevate higher

than the disappearing guns in the other batteries.

This allowed them to fire shells at a greater range of 17 miles, so an

enemy fleet approaching would come under their fire first.

On October 29, 1937, Battery Smith 2 was renamed Battery Hearn in honor

of Brigadier General Clint C. Hearn, a former Harbor Defense Commander.

This battery was gas proofed, or its magazine was.

When the gun was fired at the Japs in Cavite in 1942, the muzzle blast of

the first round blew one of the gas proofing doors off its hinges.

These batteries were located on a ridge running east-west.

West

of Battery Smith several hundred yards away on the ridge had been the 155mm gun

Battery Sunset, comprising six guns. The

ridge is named Sunset Ridge. Way Hill dropped toward the sea as does Sunset

Ridge. About 500 yards from the sea

and located on Way Hill's ridge is Battery Grubbs.

The western end of the valley between Batteries Smith and Grubbs is a rim

which drops off sharply into a deep ravine. Although the name was not on the map

we feel this was Grubbs Ravine because of

the battery on one side and Grubbs

Trail on the other side,

and always called it that.

Sunset

Ridge drops off sharply on its south side to form the north side of Cheney

Ravine; its north side forms the south side of Grubbs Ravine.

Way Hill's ridge forms the north side of Grubbs Ravine.

Grubbs Ravine descends very rapidly to the sea.

Like Cheney and James Ravines, Grubbs Ravine is a natural approach to

Topside.

There

is the railroad cut to the east of Battery Hearn which extends on to the

northwest. From this region a rail

spur comes to the northeast corner of the Battery Hearn magazine and enters a

short tunnel which leads into the magazine.

Proceeding

east along Grubbs Railroad as one nears Battery Smith a rail spur branches of

going downhill into a long tunnel into Battery Smith magazine.

Belt

Line Road passes just east of Battery Grubbs, passes into the valley between

Sunset Ridge and Way Hill where it intersects the road from Topside to Battery

Grubbs, and then over Sunset Ridge about midway between Batteries Hearn and

Smith. The road then runs

along the side of Sunset Ridge (in Cheney Ravine) within about 100 yards of

Battery Hearn. It is in a cut in

this area and is further concealed from Hearn magazine by trees.

A

short distance north of the trees concealing Belt Line Road is the beginning of

an area of desolation. Bombardment

had rendered the area of Batteries Hearn and Smith almost completely devoid of

all vegetation. Only debris and a

heavy dust cover remained. During early 1945, 28 January until 16 February, the

B-24's of the 307th Bomb Group joined by A-20's of the 3rd Attack Group dropped

3,128 tons of bombs on Corregidor, making it one of the most heavily bombed 1735

acres of the war. Other units joined in, but these were the principle units.

Actually the destroyed areas included Batteries Cheney, Wheeler, Boston,

the parade ground, and surrounding areas.

As

we advanced west along Sunset Ridge, Johnson's squad led the platoon with the

1st squad echeloned on their right covering the area down to the valley and

Grubbs Railroad and the parallel road. Lloyd

McCarter lead the way followed by 2nd scout John Bartlett.

Bill McDonald led the 1st squad as 1st scout."

John

Bartlett

"I

remember Lt. Bailey telling us to go take that hill, never knew the name.

The first time I came up out of the cut-down and on to the Hearn

Magazine, McCarter was 1st scout, I

was 2nd, and you, Bill, were third as always. I had never scouted before.

McCarter was so fast I could hardly keep up. When we reached

the top without opposition we threw hand grenades down the ventilator shaft."

Bill

Calhoun

"None

of us knew the name of this battery or Smith, either.

The magazine at Hearn simply came to be called Calhoun's Hill.

Way Hill became Bailey's Hill in the same way. We would name the

valley between Sunset Ridge and Way Hill 'Maggot Valley' in a couple of

days, so I will use this name from here on.

We

advanced in open squad column until we reached Battery Smith. No opposition had been encountered. As the platoon approached

the northwest side of Smith magazine, one of the Tennessee men, called out to

Bill McDonald that he could see a Jap looking at them through field glasses.

Bill looked to check, spotting the Jap officer's head showing slightly

above ground level. At that moment, the trooper who had called out fired his M-1, and Bill saw

the binoculars almost cut in half at the hinge. Of course the Jap died

instantly. When they got there the body was on steps leading to a door of an

underground room or tunnel (probably the oil house for the battery)"

John

Bartlett

"I

remember the Jap looking through binoculars.

We were on patrol and Aimers said "I just saw a Jap down there, and

I shot him, and I want those binoculars when we get there." The distance was so great that I didn't think he saw a Jap,

let alone shot one. When we got

there, sure enough, at the bottom of the steps lay a Jap with binoculars lying

beside him. I tried to throw a hand

grenade through the door at the bottom of the steps.

It hit the side of the door and landed beside the dead Jap and the

binoculars. Later on Aimers proved

that he anything he could see he could hit."

Bill

Calhoun

"The

flamethrower operator came up and hosed down the doorway.

Several Japs ran out and were shot down. Later, after things cooled off, and unknown to the rest of

the platoon, they opened the steel door. Moving

cautiously inside they went into a room filled with cases of whiskey, San Miguel

Beer, and a 5-gallon jug of sake."

Bill

Freihoff

"Earlier

they had found some liquor, and the best I can remember is after Bill Bailey

destroyed the loot."

Bill

Calhoun

"On the afternoon of

the 16th, before we'd undertaken any action, some troopers had found a supply of

alcohol stored in one of the houses along Senior Officers Row. Lampman recalled

it was Bacardi Rum. When Bailey got wind of the find, he broke every bottle

which some of the more thoughtful had not hidden. Now at Smith, the 1st

squad was making sure that this was kept secret. Actually, the 1st squad were

not drinkers, but it was well known that there wasn't anything better to trade,

and they liked bread. In this instance, they ended up with bread, and Major

General Marquat ended up 'without bread.'

We

occupied Battery Smith at about 1500 hours.

As I was deploying the platoon into a defensive position, a 50 caliber

machine gun opened up on us from a wood covered knoll about 100 yards west on

Sunset Ridge. Each time the gun

fired, an area of vegetation would shake. It

was very obvious where the fire was coming from.

Pfc. Benedict Schilli, 3rd squad BAR gunner, went down into a prone

position right out there on the bare concrete pad with neither cover nor

concealment and fired back. I was in the act of yelling for him to get back with

us when the 50 caliber fire ceased, it became quiet, and the vegetation ceased

moving.

Two days later on patrol we reached this

position and found an abandoned 50-caliber machine gun which had been disabled

by a bullet striking the receiver. A camouflage net laced with vegetation had

been strung up vertically in front of the gun.

The gun actually fired through the net, which was tied to stakes in the

ground at the bottom and tree branches at the top.

Whoever prepared this position had little or no knowledge of camouflage

techniques. There was also dried blood on the leaves on the ground.

The

dominant feature was the hill built over Battery Smith's magazine.

It could easily be defended because of its steep sides.

I was preparing to move the platoon up on the hill and assign the squads

their defensive sectors. After

setting up our defensive positions I intended to search the tunnel and the rooms

under the magazine. This could have

been disaster if part of the Japanese force was occupying these large spaces,

waiting in position to make the assault that night.

Later

developments would reveal that a force of some size had been in the tunnel and

the magazine rooms at some time. If

the large Japanese force was there in position to make the attack that night

they would hardly have tipped their hand to attack a small force such as ours.

Of course, had we entered their hideout and discovered their presence,

they would very likely have wiped us out with their superior force.

As we rested in our defensive position atop this great unknown, we were

all uneasy, feeling so alone and far from home,

way out near the sea, and out of sight and radio contact with our forces.

Our

apprehensions ended when a messenger arrived from Lieutenant Bailey instructing

me to withdraw to the battery to our east.

We would receive reinforcements. I

was to set up my force on the bald hill, Battery Hearn magazine, and defend it

and the immediate area. This was

about 1700 hours. I immediately

moved the platoon out for the bald hill, glad to be moving back among friends.

I

have often wondered if Battery Hearn was our objective,

rather than its brother, Battery Smith.

I did not know at the time that the Company was slated to defend Way

Hill, too. Regardless, we got the grand tour,

killed a few Japs and destroyed a 50-caliber enemy machine gun.

Our

route back to the bald hill above the magazine of Battery Hearn was along the

crest of the ridge. We walked

across the concrete pad and climbed the concrete stairs to the top of the hill.

The reinforcements were just arriving, and were substantial: two rifle squads

from the 2nd platoon, the two conventional gun squads from the mortar platoon, a

light machine gun section from the 3rd platoon of our battalion headquarters

company, and a bazooka team. We

already had a flame thrower team who had accompanied us that afternoon attached

to my platoon. 1st Lieutenant Dan

Lee had been assigned to our company that day and led the reinforcements over

from the other half of the company set up on Way Hill, about 250 yards to the

northeast. Battalion sent 2nd Lieutenant John Mara, on loan for the night, to

help out. I never understood why he

was not transferred to F Company. Even

with the addition of Lee, F Company

still only had three officers. Both

D and E Companies still had six officers at this time. The two F Company forces

numbered about seventy men in each for including all reinforcements. The RCT S-3 overlay shows F Company defending an area

extending about a mile from the bottom of Cheney Ravine to the south-west, on

northeast to the western slopes of James Ravine: and northwest of Battery Way.

A force of one hundred and forty men could not physically occupy such a

distance in a perimeter defense, nor did this appear to be the intention of

Lieutenant Brown, because he told Lieutenant Bailey that he wanted him to defend

Way Hill and Battery Hearn magazine hill. The

two forces were barely adequate for this task, if indeed they were adequate.

The

road to Battery Grubbs was closely paralleled by the railroad. The distance from our position out to the road was about

eighty yards. I placed my machine guns on the north side facing the road so that

they could place enfilading fire down the road toward Battery Grubbs.

I had the two mortars zero in on the road and railroad, for the road was

a direct approach to topside, so it was logical that an enemy attack toward

topside would probably use this road. We

had looked down Grubbs Ravine from Battery Smith and knew there could be many

enemy troops down there, though we

never thought there might be many in the Smith magazine and tunnel.

Part of Way Hill was still wooded so that Bailey and his men could not

see down into Maggot Valley; nor could they see us or we them. It was for this reason I was given the two conventional

mortars.

There were no trees or

vegetation anywhere around our position, with the exception of Cheney Ravine on

the south. About fifty yards south

were some clumps of trees. These

helped conceal Belt Line Road as it ran along the upper reaches of Cheney

Ravine. The road was also in a cut, and we did not know at the time that there

was a road there. The further down

Cheney Ravine the heavier the forest became, so that soon after passing Belt

Line Road the forest was thick and

offered complete concealment. To

us, in the late afternoon, it appeared dark and sinister, as it would indeed

prove to be.

Our

hill was a formidable position. It

was rectangular in shape, about eighty yards long (east-west), and forty yards

across (north-south). As previously

stated three sides were very steep. The

west side was so steep that concrete stairs had been built to mount this face.

The north and south side could be climbed only with great difficulty.

In addition the south side had a huge crater in the slope which made

climbing it impossible in the central area.

The east slope was a gentle slope down to the road running behind the

battery and on to the railroad cut. Obviously

this was the vulnerable side.

I

knew Jack Mara to be a very able officer. He

had briefly served as my assistant platoon leader when he joined our unit on

Leyte. Darkness was rapidly

approaching. I assigned the north

side of the hill to Mara and told him to put the machine gun section and Staff

Sergeant Charles McCurry's 1st squad in position on the north side of the hill

to cover the road. Staff Sergeant Johnnie "Red Horse" Phillips put his

mortars in position, laying them in on the primary target area, the intersection

of the road

with Belt Line Road, preparing to traverse along the road toward us.

I

did not know Lee and kept him with me to put the men in defensive positions on

the east, south and west sides. A

large ventilator shaft with large openings on each side dominated the hill.

Inside the shaft, steel rungs were set in the concrete to form a ladder to the

floor of the magazine. A huge

crater was up against the east side of the shaft.

I put my headquarters here and assigned my radio operator and two runners

to guard the shaft in case Japs came up the ladder during the night.

I had an extra runner, George Mikel. Between

40 to 50 feet east of the large shaft, was a small ventilator with louvered

sides. West of the large shaft, about fifteen feet, was another small ventilator

shaft identical to the west shaft. At the southwest part of the hill was a

concrete platform about four or five feet above the ground.

Concrete steps lead up to this floor, which obviously was the floor of a

building. I know now it was the BC

Station (battery command). Underneath it was another vent shaft which I did not

notice.

John Lindgren and Don Abbott have been back to Corregidor since we were

there, once in 1987 and again in 1989. They

went over this magazine hill thoroughly, especially in 1989 when they spent a

month on the island. They found three more smaller vent shafts. I might have seen more and forgotten them, but I remember the

ones I mentioned very well, possibly because I have snap shots of the large vent

and the two smaller vents. The

hilltop was covered with wreckage - heavy timbers, corrugated steel roofing and

even at least one railroad rail. The

south side of the hill was badly scarred by one huge crater and several small

ones. This side of the hill fell

away into Cheney Ravine. The first

trees began at the concealed Belt Line Road.

I

first put one rifle squad on the west side, one on the north side, two squads on the

east, and one on the south side. This

was not right. It was too easy. The east side was the dangerous side, but with so few Japs

why worry? I asked Lee what was

wrong with this defense. He said the weak place is the east side.

That did it. Even though it was now about dark we moved S/Sgt Leroy

Jacob's 2nd squad from my platoon to

the east side and stretched Johnson's 3rd squad out to cover the west and south

sides. Now the two 2nd platoon

rifle squads and S/Sgt LeRoy Jacob's 2nd squad of my platoon were defending the

east side. This meant about

twenty-four rifleman, including three BAR's were defending about forty yards.

The odd thing here is that in the darkness, haste and confusion, the 2nd

squad lost their BAR, Richard Lampman. Somehow,

instead of Lampman, the 3rd squad's BAR, Benedict Schilli, ended up on the east

line, so there were still three BAR's there.

Later that night we were to need every man we had back there."

Richard

Lampman

"The

BAR I spent the night with was on a cement base and the gun itself had to be

elevated and rotated by hand. The

only reason I can come up with why I got left all by myself is the confusion

that went on. The only group near

me that I recall was the machine gun - they weren't exactly close either. I don't remember being fired at directly.

Now and then a shell would bounce off the old gun barrel. I always had my

BAR set on what was supposed to be "Single Fire".

As good as I was I could never get off

less than two or three rounds at a time. Maybe

the Japs thought it was a rifle. I

often wondered if anyone else that night was by themselves."

Bill

Calhoun

"Down

in Maggot Valley by the railroad tracks lay two wrecked trolley cars on their

sides, their floors facing us. Looking

to the northwest to Way Hill, where Bill Bailey's force was in position, all we

could see was a wooded hill which had escaped the clearing of the heavy

bombardment. We could not see them, and they could not see us. I was told that D Company was at Battery Cheney.

This battery was to our south, about 1000 yards away on the other side of

deep, heavily wooded Cheney Ravine. D

Company was strung out on a long, narrow ridge which ran from Battery Wheeler to

Battery Cheney. The battery and the ridge running back toward Battery Wheeler

could be easily seen from our hill, but the distance was too great to see the

men individually. "Down

in Maggot Valley by the railroad tracks lay two wrecked trolley cars on their

sides, their floors facing us. Looking

to the northwest to Way Hill, where Bill Bailey's force was in position, all we

could see was a wooded hill which had escaped the clearing of the heavy

bombardment. We could not see them, and they could not see us. I was told that D Company was at Battery Cheney.

This battery was to our south, about 1000 yards away on the other side of

deep, heavily wooded Cheney Ravine. D

Company was strung out on a long, narrow ridge which ran from Battery Wheeler to

Battery Cheney. The battery and the ridge running back toward Battery Wheeler

could be easily seen from our hill, but the distance was too great to see the

men individually.

They were not

incorporated into a perimeter either. Their position was a narrow finger jutting

out away from our main defenses. This

was an unsupportable salient. C Company was nearby to their east at Battery Wheeler, but being at the base of

the salient could not support D Company. Despite

being in a position where time was needed to set up a defense which covered all

routes of approach, D company were not given that time. I believe battalion gave them their

orders even later than they gave F company theirs.

It is hard

road to hoe for those of us

who were at the lower level to understand why two companies were pushed well out

from Topside into isolated positions with no provisions made far any fire

support. Moreover, there was no way to call for fire support.

At the company level our radio net was closed at dark, and our orders and

standard practice was clear, and had been so since Noemfoor - under no

circumstances were we to open a radio until dawn. No wire was strung to D or F Companies that night, either.

Every

platoon leader, and those above were given a "Special Map" of

Corregidor Island, 1:12,500 marked with pre-designated numbers and letters, (e.g.,

Battery Hearn was #19, the junction of Belt Line Road and the road in Maggot

Valley was #25, Battery Cheney was #12 and so on.) When the Japs appeared at

point #25 we should have been able to notify higher headquarters who could have

called for naval fire from the cruisers and destroyers lying off shore waiting

to give fire support, or they could have called in our 75mm howitzers, or our

81mm mortars. This was not done.

But

we were muzzled.

We

had also been lulled into over-confidence by the failure to correctly estimate

the number of Japanese troops on the island. The

prevailing thinking in our combat team when we jumped was formed from a G-2

estimate of 850 defenders. By now, at the higher levels of command, it was known

that more Japs had been counted killed than the original G-2 estimate had

pronounced upon the island. It was also known to them that our units from

Malinta Hill to western Topside were meeting heavy resistance, so a warning down

to the companies that "a heavier Jap force occupies the island than had

been originally thought" should have been

issued. Certainly the disposition of the 2nd Battalion's D and F Companies was unfortunate and should not have happened, but the confident attitude pervaded even

Topside, especially Topside, that night, which had no reserve force. The scheme of defense had

resulted in a number of strong points, and on this night, the Japanese we weren't aware of were about to test our strong points.

Just

after dark two mortar rounds struck the top of our hill, but did no damage.

Sgt. "Red Horse" Phillips and Burl Martin thought they were fired from a mortar near

Grubbs Railroad, from a position just after it turns toward Battery Grubbs and bends out of

sight. They fired five rounds into this area and we heard no more.

Lee and I were so busy placing the rifle squads into position that we

were unaware of the incoming Jap mortar rounds or of our counter-battery fire.

Perry Bandt and John Bartlett were

in the 3rd squad and on the south

side."

John

Bartlett

"I was aware of the mortars though. Bandt

and I were thinking that there was very little resistance left on the island and

we decided not to dig in for the night. About dark a mortar opened up on our

position, three or four rounds were fired.

Red Horse and I were talking about this and wondered why they quit

firing. Needless to say Bandt and I

dug in quickly."

Bill

Calhoun

"Bartlett's

statement about his and Bandt's frame of mind regarding the Jap resistance being

negligible typifies the attitude brought about by the G-2 estimate of 850 Jap

defenders.

About

2200 hours we started to hear them coming.

Along our eastern perimeter,

we could hear Japs shouting in the area, we thought, of the railroad cut. It

seemed to start with an individual shouting and the group would chant a

response. This would increase in volume until it reached a crescendo.

The all out Banzai would follow.

There is sometimes a

lot of jocularity, sing-song and camaraderie about being willing to travel to

the gates of hell with one's buddies, but truly each of us one's knew that in a

short while the gates of hell were marching up the valley towards us.

They were yelling and shouting, marching up the road along

Maggot Valley. This seemed to be the signal for a Navy star shell to explode

overhead and illuminate the area, though the Navy's

timing was simply and randomly fortuitous. The front of the Jap column could be

seen clearly near the junction of Belt Line Road and the road,#25. A

long line of a column of fours followed, proving at last

to us that the intelligence estimates were carefully crafted fantasy, rather

than military science.

It

was about 2330.

They seemed to

be trying to incite fear into us by their shouting and chanting, and were successful. Any

rifleman, put in one position and ordered to stay there, who says he didn't have

doubts as the gates of

hell came up to meet him that night wasn't there. We'd all heard and

retold the stories of Jap tactics in past battles, such as Bloody Ridge on Guadalcanal when the

Japs charged chanting "Marine you die!", "Banzai!", "Totsugeki!"

(charge), "Blood for the Emperor!" flashed again to our minds,

and we knew that shortly there would be a lot of death to be done. Arranging for

things to happen ("

Todd,

get over to Johnson and get a bandolier of ammo from everyone of his riflemen

and so many BAR clips," "Crawl up to Lee and Phillips and check

the situation," and "Send Mikal over to the north side and check

on the 1st squad and the machine guns" etc.)

kept me so

preoccupied though, that there was no time to lose concentration or presence of

mind. At the end of those thousand hours, when dawn's early light came, there

was no one among us more relieved than I.

Proving

it was not a vision, several subsequent star shells floated eerily over the

landscape. This was a battalion sized unit, 500 men or more. They were close enough for us to see that

some were sick and throwing up, yet they came.

We felt they were drunk. The booze was certainly plentiful enough.

Our

firepower was cutting swaths into their ranks, and still

they came. Groups would crumple from the explosions of our 60mm mortar

rounds scoring direct hits in the road,

and those still erect would close up ranks and keep on coming.

Soon our machine guns were also cutting swaths in their ranks.

Each

of the two mortars had 40 to 50 rounds of ammunition, but all too soon the

supply was exhausted.

Until

that hellish sight, there had been no evidence to suggest that there were so many Japanese remaining

on the entire island, yet it was no

accident that our mortar defense reserves were so robust.

We probably would not have survived with less, and if the command credit

should have gone to any single man that night, it should have gone to our

Company Commander, Bill Bailey, who was not taken off guard.

He'd planned for the worst, as a good commander should, and had laid in

to both positions a large amount of ammunition for the night.

Bill just never did toot his own horn, he was busy doing his job.

Life isn't fair, and neither is recognition in war, but he sure deserved a

Silver Star that night. He just wasn't the sort who'd see himself awarded one.

Recognition

of uncommon valor that night did come to one man, and though it interrupts the

recalling of the fight, I will tell it now because this recognition was to the most extraordinary

warrior I ever knew.

Two Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded

arising from the retaking of Corregidor, one for action on the USS Fletcher during

the pre-invasion bombardment and the other, the only land based award, was for

our first scout that evening.

Being

in the 3rd squad, Private Lloyd G. McCarter was initially on the south side of

the hill. A few of his squad were on the west side of the hill.

Red Horse was with the gun at the small east ventilator.

McCarter

had

seen some of the Japs were getting

past, and moved to the northeast corner by the 'hump' formed where the tunnel

entered the magazine."

JOHN "RED HORSE" PHILLIPS

"I

saw McCarter cross the hill from his position on the south side of the

hill and go down near the "bulge" at the northeast corner of the hill.

The "bulge" was the trolley

tunnel which ran into this corner of the hill, supplying

the magazine with heavy munitions and equipment.

McCarter,

as a 1st scout, was armed with a Thompson Sub Machine Gun. The distance from the hill to the road was too great for

effective fire for this weapon. On

his own volition, and without anyone else's knowledge, McCarter climbed his way

down the steep slope and took up a position in a shallow gulley by the side of

the road, opposite the

upturned trolley cars.

From this position he fired directly into the enemy

column. He made several trips back

to the hill that night to obtain more ammunition, changing his Thompson for a

BAR when it malfunctioned and later, when the Browning failed, to exchange it for an M-1 Garand rifle.

The BAR had become available after Schilli was wounded.

Finally even the Garand malfunctioned, its operating rod splitting!

How many rounds did he fire to cause this tough weapon to malfunction in

such a manner?

When

heavy enemy traffic going up the road had long ceased, McCarter commenced

to dueling with Japs who had taker up covered

positions around and under the trolley cars.

McCarter, short and stocky, yelled and laughed at the enemy when he was

engaged in combat, for he was one of those rare individuals which combat

transforms into a state of great exhilaration, so much so that they seem

absolutely fearless. I had seen this in him before, and

McCarter was no different that night."

BILL

CALHOUN

"The Navy flares continued to

light up the night, but in no particular pattern, they weren't constant. The

most frequent firing took place from about 2000 hours until around 0200 to 0300

hours, though. A number of Japs did get

past us, and past McCarter, evidently assembling in

the area of the rail and road junctions to our northwest toward Way Hill.

Some of them attacked Bill Bailey's force on Way Hill, and others

attacked our east perimeter. A few went on to Topside.

After

repulsing the first attack, which

came at about 2330 hours, all was

quiet for a while. After an hour or

so the chants began again and continued as before, reaching a crescendo, and

then the tide of death would flow in again.

Our confidence remained high,

though as the night drew on, there was an ever growing concern that our

ammunition might not see us through to the morning. Sometimes it would go dark maybe fifteen minutes at a stretch.

It seemed black as pitch for so long as time passed. "Where are the

flares?"

The third attack came

in the same manner as the first and second attacks, and was repulsed, but we were now

to the last of our ammunition. Johnson gathered up ammo from his 3d squad. Bayonets were fixed, and trench knives readied.

Nor did it help to have the SCR536 radio, for the net was closed.

"Where are those

flares?"

Near dawn the chants started again. The situation was critical.

Fortunately for us no attack

came. Dawn broke shortly, and the

phrase "immense relief" cannot do justice to our feelings.

Around dawn

McCarter was hit hard by a bullet in the chest,

and when it was light, he could be plainly seen in the position where he lay

down by the road. It looked to us from a ways off he was dead. Some men

went down, even though there was some fire still from a Nambu LMG, and only then was

he carried, or rather dragged,

back up the hill to its relative safety,

into a large crater near the big ventilator.

I

figured it would be mid-morning before we could get him through to Topside, and

with a bullet entry near the middle of his chest, I was worried about him going

into shock.

Our Medic, Pfc. Roy

Jensurd, had used his supply of blood plasma long before. I

went to McCarter several times to reassure him we'd get him out as soon as we could.

Each time

he told me not to worry about him, that he was doing all right. I never saw any symptoms of

shock. He was tough and complaint was not in his vocabulary."

Richard Lampman

"The next thing I can

remember was that two or three of us (I don't know who was with me) came upon a

group milling around, trying to get McCarter out of the ravine (RR track area).

The road was wider than most with steep walls on both sides. I do not

remember where it went. He was on a stretcher.

The first I knew he had been wounded.

A Jap came out of one of two large concrete double doors, open about a

foot or twenty inches behind them and threw a grenade.

It arched up and hit the steel pole that carried the electric wire and

dropped back on him. Three others and myself grabbed the stretcher and went out

of there in a hurry!! I don't know

what the rest did.

Some

of us got to look inside a day or two later. I have never seen so much black gun

powder!! It was in large bins like

we used to store oats and wheat on the farm.

We were in some other places loaded with G.P. only not so much."

BILL

CALHOUN

"At

dawn of the 19th I reported our situation to Bailey.

We were cut off to the east by the Japs in the railroad cut, and to the

north by Japs under and around the trolley

cars.

They had a Nambu LMG. Any movement

drew fire from them and the riflemen. We were out of ammunition. We had several

wounded who were in real need of medical attention. Pasquale Ruggio, of the 2nd

platoon, was hit by rifle fire from the direction of the rail-road cut and

killed. Pfc Lawrence Rainville,

mortar platoon, was wounded too. The mortar men, Sgt. Phillips, Burl Martin,

George Montoya, the young Richard "Tropical" Peterson▼, Virgil Short,

and others searched through the dozens of empty mortar shell cartons and found 5

or 6 rounds.

After

Ruggio was killed they fired these rounds at the "ditch", or railroad

cut. They thought they'd put every round in it.

Even

the .50 cal was fired towards the cut.

In

truth, there was a crater against the railroad cut which we could not see, and

there were over a dozen Japs taking very effective shelter in it. These were the

Japs who were firing at us. Those in the cut were unable to climb the high,

sheer walls to get into position to fire at us.

The

sun was up now, and the SCR 536 radio was powered up. At this point the CO of D Battery contacted me by radio.

His thin radio voice was quizzing me,

"I can see about 300 yards to

the east north-east of your position, looking straight down the cut, and see a

group of men in the cut. Are they enemy?"

"Affirmative.

They have us cut off from Topside," I responded.

"Well,

we'll soon take care of that," was his assurance.

Only

when the D Battery's 60 mm mortar battery delivered an awesome

amount of fire down the cut, where it created a carnage exploding between the

concrete walls, was the problem eliminated. Later we would find the bodies so heaped up and mutilated that

we could not get an exact body count.

We

evacuated our wounded. Pvt. Lloyd McCarter, Pfc. Benedict Schilli, Pfc. Richard Aimers, Pfc John

Albersman, Pfc. Lawrence Rainville, and one of the LMG

section men, possibly two, were wounded. All the wounded were litter cases,

which gave us some problems. S/Sgt Donald

E. White from the 2nd platoon had had moved his position on the southeast

corner forward several yards in order to better see the enemy and to control his squad. For this act of

bravery he lost his life. Pfc. Pasquale A. Ruggio, also of 2nd platoon, was

a fatality. The casualty list belied the serious situation we had been in, and

how close the Japanese had come to defeating us.

The ground is littered

with Japanese weapons and one of our conventional 60 mm mortars. We had both

of them out there. The direct fire 60 was over with Bailey's force on Way

Hill. From left to right are Richard "Tropical" Peterson (15 years old), Bill

Calhoun, George Montoya holding a Jap 50 cal. MG, Virgil Surber, and Burl

Martin holding a Jap 50 cal, MG. All the men with me are in the mortar

platoon.

The

Japanese had suffered dearly for their Bushido. The next day, the 20th, we

counted and estimated about 315 corpses, including about 200 dead along

Maggot Valley. We had to use some estimates, because the Japs had dragged many

bodies into craters, and we were not about to remove them just to count them.

There ere two very large craters on Grubbs Road which were filled to the top, as

well as several small ones. There

were 70 bodies in between our east defenses and the crater, about 30 down in the

railroad cut, and 15 in the crater adjoining the cut. Bill Bailey estimated that

his force on Way Hill had accounted for 135 more.

We destroyed or captured at least 13 machine guns.

We destroyed a HMG (Schilli's the afternoon of the 18th at the wooded

knoll, we brought six 50 cal HMG's from the valley to the top of the hill along

with five 30 cal LMG's ( three Lewis type and two Nambus) and one Nambu was

destroyed under the trolley cars. In addition there was a probable. Jack Mara tells me of a machine gun located up on Way Hill

behind the trolley cars some distance. This

gun opened up on us during the night. Qur

LMG's soon silenced this gun. We

did not get up there so we did not know if the gun was still there.

I

still have several snapshots of these guns.

In addition to John Bartlett and Perry Bandt bringing up guns, some of

the mortar platoon brought up guns. It

took two men to carry the HMG's. The

Japs tied wire or cloths around the barrel near the muzzle so the man in front

would have something to carry the gun by. I

have no memory of how we disposed of these guns.

We probably carried the LMG's with us, but I doubt if we carried the

HMG's.

Our platoon had prevailed against a multitude of attackers in exchange

for relatively few casualties on our side. This was due to several factors.

Firstly, we held a formidable position. Secondly, our men were placed to take

the best advantage

of their position. In the face of an overall laxness, Bill Bailey had exercised great foresight in taking

precautions, seeing that both

strong points were adequately manned and supplied with extra ammunition.

Fourthly, we had to thank the

mindset of the Japanese officers, who simply failed to comprehend that the

principles of Bushido were no substitute for the principles of a good offensive

action. Their staggering incompetence to the task still stupefies me, and the

waste of the duteous servitude of their lower ranks appalls even all these years

later. Fifthly, the �lan of the U.S. paratrooper, as finely attuned

to the necessities of close combat as our years in training had been able to

make us � the best! "

THE JUNGLE ALWAYS

WINS

Meanwhile there had been

much action over on Bailey's

Way Hill.

►"Tropical"

jumped on Corregidor at the ripe old age of 15. He survived Corregidor

and celebrated his 16th birthday in the hills of Negros. When his age was

discovered, he was swiftly sent home.

▲

|